There was a time when staying still felt like survival.

In earlier books, I built rules. Borders. Systems. Characters.

They weren’t there to control the world; they were there to hold it together. To keep parts of it from bleeding into one another until I could breathe again.

But Book Three exists because it stopped being enough.

This book was written in my third year of therapy, a year when naming things was no longer the hard part. By then, I had language. Insight. Awareness. What I didn’t yet have was movement that wasn’t driven by urgency or collapse.

I had learned how to endure.

I had not yet learned how to choose.

When the Past Shifted Shape

The diagnosis of dyslexia didn’t fix anything.

It reframed everything.

It happened quietly.

My psychologist had asked me to keep a journal. I did, but I wrote stories instead.

Two books, written as narrative because that was the only way my thoughts would hold together without fragmenting. I brought them into therapy not as literature, but as evidence, a way of showing what I couldn’t explain directly.

She read them carefully.

Not for plot.

For structure.

And then she said something that stopped time for a moment:

“You know this reads like someone who has been compensating their entire life.”

The diagnosis didn’t arrive as a revelation.

It arrived as recognition.

The Cost of Constant Translation

Suddenly, the effort made sense.

Not effort as discipline or ambition, but effort as constant translation.

The invisible work of holding thoughts in place long enough to shape them.

The vigilance required to keep meaning from slipping through cracks no one else seemed to notice.

The exhaustion, too, took form.

Not the kind that comes from doing too much, but from doing everything twice: once to understand it internally, and once again to make it legible to the world.

The way staying in place always felt like swimming upstream, not because I lacked strength, but because the current was never designed for how my mind moved.

Endurance had never felt neutral.

It always carried a price.

From Moral Failure to Evidence

What I had mistaken for resilience was often compensation.

What I had called discipline was frequently survival strategy.

Overpreparing. Overchecking. Rereading until words blurred.

Building systems around myself without realizing I was doing so, just to stay afloat in spaces that assumed ease where there was none.

Nothing about who I was changed.

My capacity didn’t suddenly improve.

I didn’t become “better” at anything.

But the past reorganized itself.

Moments I had filed away as personal failures loosened their grip.

The chronic tension around tasks others found simple.

The shame of needing more time, more structure, more silence.

The instinct to endure quietly, even while asking careful, persistent questions to understand what I didn’t yet have language for.

They stopped being moral flaws.

They became evidence.

Not of weakness, but of adaptation.

Of a mind that had learned to move sideways when forward was blocked.

Of a system built not for comfort, but for survival.

And once seen, it could no longer be unseen.

Containment Was No Longer Enough

By the time I was writing Book Three, containment had done its job.

In Book Two, containment was the work.

Boundaries. Agreements. Rules that prevented collapse. A system where pain could exist without consuming everything. But containment has a limit.

There comes a point when the rules I built to survive begin to restrict my ability to grow. When staying within them requires more energy than moving beyond them. When endurance turns into erosion.

That was the year I was living in.

In my second year of nursing college, I made the decision to pursue psychology and enroll the following year.

During my clinical placements as a nurse in a children’s hospital, especially in orthopedics and surgery, I learned that pain does not wait for you to be ready. I often stayed beyond my required hours, unable to step back into my own life while children continued to suffer.

Skill alone was never what I wanted to offer patients.

What I wanted was to understand them.

That is why I enrolled in a psychology program. Understanding meant learning how to move toward people, not only away from my own limits, and I could no longer do that by staying still.

Movement, Not Escape

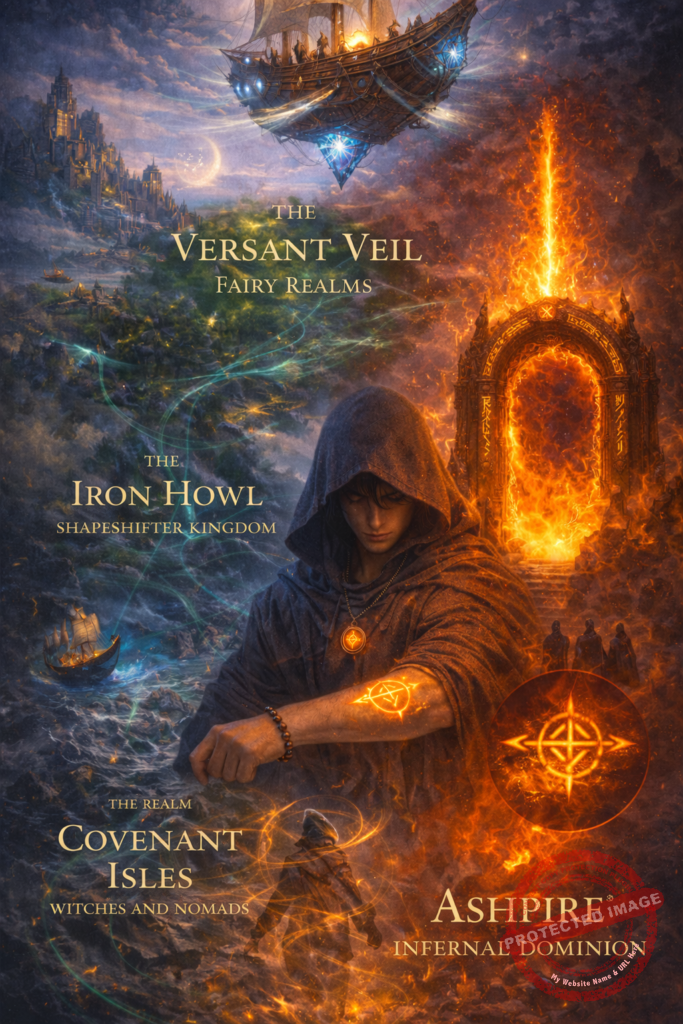

Transportation systems in this world are not conveniences.

They are not shortcuts.

Nor are they about running away.

They exist because movement became necessary.

This book was written in a year where motion stopped being reactive. Where I learned that leaving a place: emotionally, cognitively, structurally, doesn’t mean abandoning it. It means acknowledging that what once protected you may no longer be safe.

Movement became intentional.

That’s why every form of transportation in this world has rules. Costs. Permissions. Limits. Witnesses.

Not because motion should be controlled, but because it should be chosen.

Why Transportation Exists at All

Rules taught me how to stay.

Movement taught me how to choose.

I had built transportation systems when I accepted that not all growth happens in place, when I understood that endurance by itself is not a virtue, and when I realized that sometimes the most responsible thing you can do is admit that where you are: mentally, emotionally, structurally; is no longer safe.

These systems are not about speed.

They are about agency.

Some paths require clarity before you can take them.

Others require permission.

Still others demand witnesses.

Many take time.

A few refuse to be rushed.

And some only open when you stop mistaking stillness for strength.

Setting the Journey

This series of posts is not just about how characters move between realms.

It’s about how I learned to move between parts of myself without erasing any of them.

Book Three begins when containment breaks its silence and asks a harder question:

If you can move, how will you choose to do it?

Blog Categories*

*This blog extends ideas from the novels, reflections, process writing, and lived experience behind the stories.

Leave a Reply